By Benjamin Irvine (@econbecon)

In the absence of adequate income support or rent relief programmes from the government, Rent Strike Committees across Spain are bringing renters together to negotiate with landlords and enable people to stay in their homes at a price that gives them room to breathe.

Precipitated by the coronavirus lockdown and the large — and in many cases total — loss of income this has implied, thousands of renters across Spain have been on rent strike for 2 months. More than 16’000 households have signed up to a national Rent Strike campaign since it was called on the 30th of March. Galvanized by the memory of those who lost their jobs and then their homes during the 2008 crisis and the austerity that followed, the strike has been a pro-active step taken by the renters movement to ensure that the costs of this crisis won’t be pushed onto the poor and working class again. The slogan is simple: “No cobramos. No pagamos” (“if we don’t earn, we don’t pay”).

The movement for housing justice in cities like Barcelona has in recent years been cutting its teeth resisting touristification, the deliberate liberalisation of the rental market and flows of speculative real estate investment from tax-haven domiciled vulture funds. Between 2013 and 2019 rental prices increased by an average of 50% nationally — and over 50% in cities like Barcelona and Palma, according to a report by the Bank of Spain. Over the same period, the nominal value of median incomes increased by just 9.5% and 6.9% for the lowest 25% of earners, according to Eurostat. Traditionally high rates of owner occupation are declining and more people are renting — in large part because employment contracts have become increasingly insecure — which has meant fewer people are able to access mortgages. The low stock of socially rented housing (one of the lowest in the EU) has been in gradual decline whilst the number of residential properties converted to short term holiday lets has reduced the supply of housing and pushed up rents. A substantial chunk (6.8%) of Barcelona’s rental housing stock is listed on Airbnb, which is estimated to have increased rents by an additional 7% in the most affected neighbourhoods.

It was under these conditions that neighbourhood housing unions and the Sindicat de Llogaters (union of renters in Catalan) — key actors in the current Rent Strike campaign — were formed. Following the introduction of policies designed to to “stimulate” the rental market through reduced tenancy lengths and the granting of tourist licenses for the conversion of housing into holiday apartments, the Sindicat de Llogaters was founded in 2017. The organisation took key lessons from the PAH (Platform for People Affected by Mortgages) that organised groups of neighbours had the power to physically block evictions and set up a similar organisation for the issues facing tenants. The tools and strategies they have developed have been central to how the Rent Strike is being organised.

There has been a progression in the way the Sindicat works, says Javi, a 32/year/old software engineer active in the Organisation Committee of the Sindicat de Llogaters in Barcelona. The union initially functioned as a campaigning platform to denounce the issues facing tenants and formed part of a coalition calling for 30% of all new developments to be dedicated to affordable, social housing — a demand which successfully entered into planning law in Barcelona in 2018. The Union also started organising tenants facing rent hikes when vulture funds bought their buildings: “Then a year after the sindicat’s foundation, we launched the Ens Quedem campaign, which means "we’re staying" and this is key to how we work right now”, Javi tells me. “The whole campaign was about doing these assemblies that we now do every Friday, in which people explain their problems and we do a collective assessment. We don’t provide a customer service, we don't have like a window and a queue and you pay your membership and then we solve your problems, it doesn't work like that. You come to the assembly, you explain your problem, and the people help each other.”

The union also started focusing in on a strategic type of problem: tenants whose contracts were ending and whose landlords were telling them they had to accept substantial rent increases to stay. For these cases they have developed something of a blueprint. The first step is for the tenant to investigate their landlord. How many properties do they own? Are they a fund or a bank? The second step is to speak with the neighbours or other tenants of the same landlord to see if they are facing the same problem. Once the tenants are organised and have chosen they want to stay the union initiates a negotiation:

“the sindicat sends a letter or an email to the landlord, saying ‘okay this person is not alone. He or she is a member of the of the tenants union and as such she can count on all of the protection or all of the energy, all of the tools that an organisation with nearly two thousand people may give them.’ We try to not threaten people or anything but just we just tell the landlord, ‘hey, this person is not alone’ and they’re not going to tolerate being kicked out because they can’t afford the new price.”

And if nothing is agreed by the time the contract ends there is a final element to this strategy: “you don't pay the increased rent that your landlord is trying to impose on you, but you keep paying the same exact rate that you were paying. That's for two reasons. One is to bargain and to explain to the landlord that we want a negotiation and this is what we offer. The other reason is that if you stop paying you will end up with an eviction in two, three months. But if you continue paying the same rent, there will be a legal process but it will be to determine if your contract has ended. And it will be longer, nine-to-twelve months, and that's time that we use to negotiate with the landlord.”

These tools of assemblies, a process by which renters self-capacitate themselves and the experience of rent disobedience in bargaining with landlords is central to how the rent strike has been organised and spread. The Sindicat de Llogaters and Sindicato de Inquilinos in Madrid acted quickly as the prospect of a prolonged lockdown emerged. They reached out to other housing groups but also labour unions and social movements across Spain and formed a campaign for a Social Shock Plan. Against the usual economic “shock treatment” of austerity they called for a social “shock” or “crash” plan, including the suspension of rents but also the socialization of private healthcare resources and a Universal Basic Income.

This campaign had been calling for the suspension of rents for two weeks when the coalition PSOE-Unidas Podemos government finally announced measures to alleviate peoples inability to pay rent amidst the unprecedented shutdown of the economy. This included an automatic six-month extension of all contracts that were coming to term during the state of alarm and a six month suspension of evictions, which the movement claims as victories. The government did not however suspend rent and instead proposed advancing “micro-loans” to renters to pay their rent with credit, to be paid back over the following years. Landlords with ten properties or more may choose between offering a 50% reduction or a “moratoria” on rent — with the arrears to be paid back in the future and only in the case that tenants can sufficiently demonstrate that their economic vulnerability was due to covid-related social distancing measures. The means testing process resembles a “vulnerability bingo” with poor odds for most renters. It goes without saying that renters struggling to pay now due to losing a job or being temporarily laid off with reduced income were already stretched tight. They aren’t going to be able to afford increased rent payments in the future. As Javi describes the logic of the campaign, “if the productive economy is stopping, then non-productive economy or the rentier economy should stop as well.”

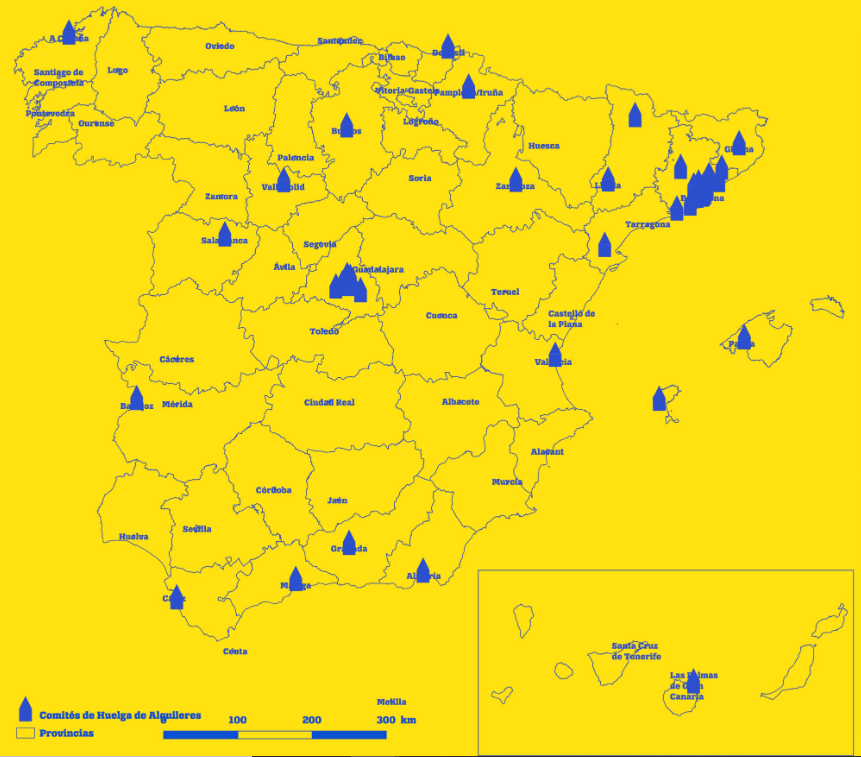

Following the announcement of these measures the campaign called for a Rent Strike. A template letter requesting rent cancellation during the state of alarm was published on the campaigns website, one for the landlord and another for the housing ministry. Rent Strike Committees were set up and those signed up to the campaign have been linked up to their nearest housing group, sindicat chapter or — where there was previously no tenants union — with each other. Despite the fact people have been largely communicating online, according to Javi, it was important to organise people by neighbourhood: “we know that this is going to be a long struggle. So after the quarantine it makes sense to have people organised locally”. Within the weekly Rent Strike Committee video-assemblies, “the idea is to address doubts, the questions that people may have and try to negotiate with landlords. We always suggest to try and make the landlords understand that there is a crisis coming and they should negotiate a new price that people are able to pay because, eventually, all prices are going to go down. Everyone can’t be evicted because that's going to be a mess.”

A key function of the assemblies is providing reassurance to people feeling anxious about breaking contract terms and entering into a legal dispute. Experienced union members encourage newcomers and even other seasoned members to remain calm. It is, after all, the landlords that have more to worry about if the issue is not resolved quickly. They reassure people struggling to pay the rent that it’s likely that they can access free legal representation. They explain that it’s very rare that the landlord brings the case to court: “what they want is for the renter to pay or to leave, whilst what the sindicat struggles for is to pay what we can”. With automatic six-month lease extensions, judicial processes paralyzed and evictions officially suspended for “vulnerable households”, the mood in the video assemblies I attended has been buoyant.

Nevertheless, the effect on rental prices two months into this crisis is muted. Many in the Sindicat, including Javi, are sceptical about the neutrality of the country’s main property websites: “they don’t want to accept that prices are coming down”. In February, Spain’s antitrust watchdog opened an investigation into the country’s largest property platforms for price fixing. These include the Idealista behemoth whose price data is frequently referenced to supplement patchy public statistics on the rental market.

If sales prices do come down, there is a danger that, like the last time the property bubble temporarily burst, international investment funds swoop in to buy up on the cheap. “We're preparing. We were already warning against these international actors before and we know them better than ever”, Javi assures me.

Another battleground and possible avenue for the renters movement in Spain as a result of the covid crisis, Javi suggests, are tourist apartments. Once part of the rental housing stock they’ve lain empty during the crisis and perhaps won’t find a tourist market for some time: “We've seen how thousands of units or apartments have been vacant during the duration of this crisis because they used to be Airbnbs and tourist apartments. Lots of people including the sindicat are going to demand that these homes are returned to the the housing stock as public housing. I think that there is a lot of backlash to the tourist apartment thing, not only in Barcelona or Madrid, but also in Lisbon and many other cities”.

The Spanish government has not suspended rent but — thanks to the strength of renters unions and the Rent Strike campaign — many people have won reductions to their rent from their landlords and are negotiating new prices they can afford. Against the charge that this is not a rent strike, but just people unable to pay, Javi concedes: “that's fair enough. We see this not as a tool that we use in an ideal situation but as a context. We are organising people to stop paying at the same time in a coordinated manner. Going to these committees and coordinating everything, it's also to create a movement, to grow the movement of tenants so that they are strong political subjects and that they can bargain better for their rights.”

Benjamin Irvine writes about the economy, lives in Barcelona and is a member of the Sindicat de Llogaters

22 June 2020